TR Encyclopedia – Politics and Government

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, founded in 1788, began its life as a fraternal organization for craftsmen, lobbying for universal male suffrage, protection against imprisonment for debts, and the implementation of lien laws to protect craftsmen.1 By the mid-nineteenth century, however, it had begun to take on its more infamous role as the quintessential Democratic political machine under the leadership of William “Boss” Tweed. Under Tweed’s leadership, Tammany Hall would take in immigrants–mostly Catholic Irishmen and women–find them work and housing, and support them in legal matters in exchange for votes supporting Tammany Hall’s policies and candidates.2 With this bloc of voters firmly in favor of Tammany Hall, Boss Tweed was infamous for his rampant corruption in the city of New York. He padded out city budgets and pocketed the rest, gave out bribes to judges in exchange for favorable rulings, and (according to some estimates) brought in up to $200 million together with his cronies.3 For all this corruption, however, it is difficult to characterize Tweed’s actions and the actions of Tammany Hall, as wholly negative, as many of his supporters did not know of this corruption, and Tammany Hall played an important role in helping the burgeoning immigrant community of New York. He would make sure immigrants could find work, eat, and even be provided money for coal to heat their homes.4 Eventually, however, the corruption of Boss Tweed began to become more broadly known as newspaper articles were published detailing the extent of the crimes he committed. After a failed bribery attempt and two trials, Tweed was finally convicted of over 200 crimes in 1872.5

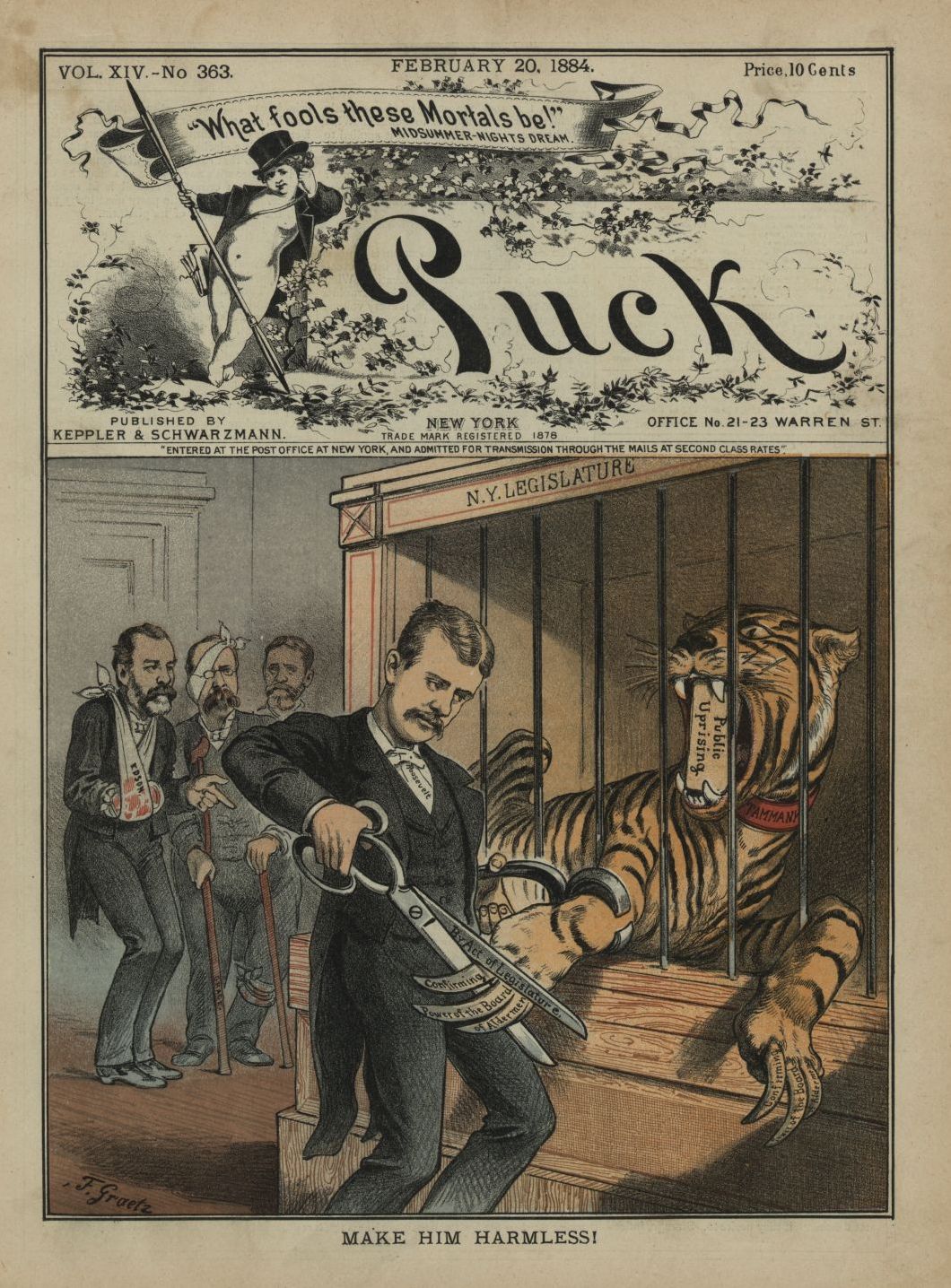

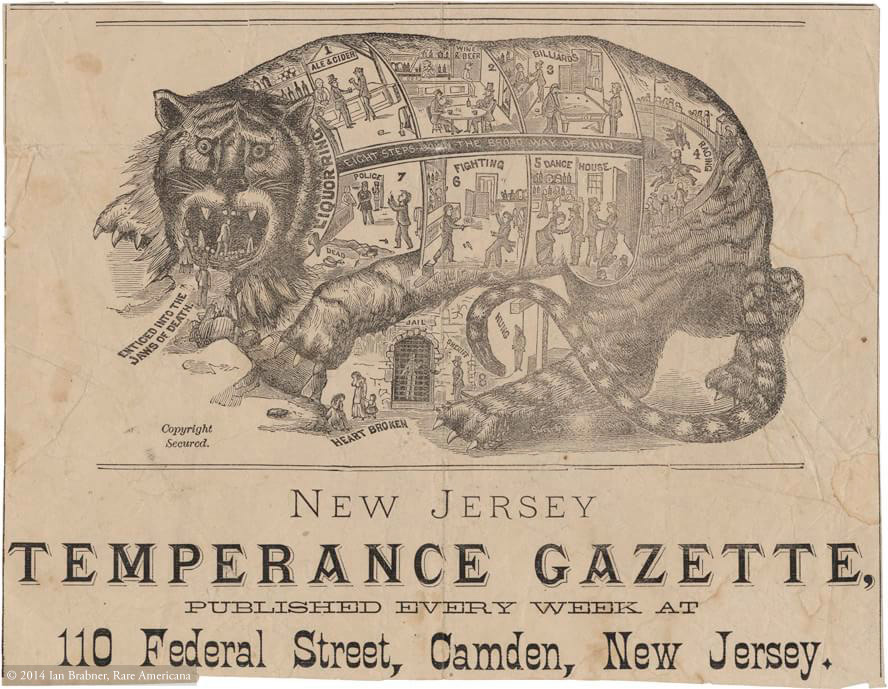

Although Tammany Hall had done a lot of good for immigrants in New York, it had also allowed the city to become a caricature of corruption and vice, and had run down the reputation of the New York City Police Department which had allowed much of it to happen. During Theodore Roosevelt’s term as Police Commissioner, from 1895-1896, he sought to reform the NYPD and clean up its act. He would institute “midnight rambles” which were nightly inspections of officers on duty to make certain they were carrying out their duties.6 These “rambles” also brought Roosevelt face-to-face with the broader populace of New York, leading him to remark, “I get a glimpse of the real life of the swarming millions.” Roosevelt would later carry this familiarity with the broader public into many of his policies aimed at giving the common person a “square deal,” and making sure that they were treated the same way under the law that the wealthy and powerful were. Although he was extremely popular among the people of New York for his efforts to reduce corruption, he lost favor among many poor Americans, particularly German immigrants, for enforcing a law prohibiting the sale of alcohol on Sundays, which at that time was the only day many people had available for rest and relaxation.7 Such strict enforcement of laws gave Tammany Hall, who drew most of their supporters from the immigrant population, a weakness to exploit, turning the issue into a scandal. Eventually, with many of his reform efforts frustrated, Roosevelt left the office of police commissioner for more fertile political ground, but not before a ferocious battle that would see newspapers demonize Tammany Hall as an encourager of vice, as seen in the political cartoon below.

In spite of Roosevelt attempting to “clip the tiger’s claws,” both as a New York Assemblyman and as New York City Police Commissioner, Tammany Hall would remain a key factor in New York City politics for many decades to come. Ultimately, it is impossible to characterize Tammany Hall as either wholly good or bad, and it must be treated with more nuance; while the political machine brought many benefits to its constituents in New York City–providing services to those in need when the city was either underfunded or unable to provide them and allowed the ease of naturalization of immigrants into American life–it also became the key example of machine politics and corruption during the Gilded Age, and remains so to this day.

1. Vos, Frank. “Tammany Hall.” Tammany Hall-Encyclopedia of New York City, virtualny.ashp.cuny.edu/EncyNYC/tammany_hall.html. Accessed 25 Sept. 2024.

2. Ibid.

3. Bill of Rights Institute. “William “Boss” Tweed and Political Machines”. Accessed on 9/27/2024. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/william-boss-tweed-and-political-machines/

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Klein, Christopher. “How Teddy Roosevelt Ascended in New York Politics.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, 29 Apr. 2022, www.history.com/news/theodore-roosevelt-new-york-politics-governor-police-commissioner

7. Ibid.

Entry contributed by Isaac Baker – Theodore Roosevelt Center Student Employee