TR Encyclopedia – Foreign Affairs

Panama Canal Treaty

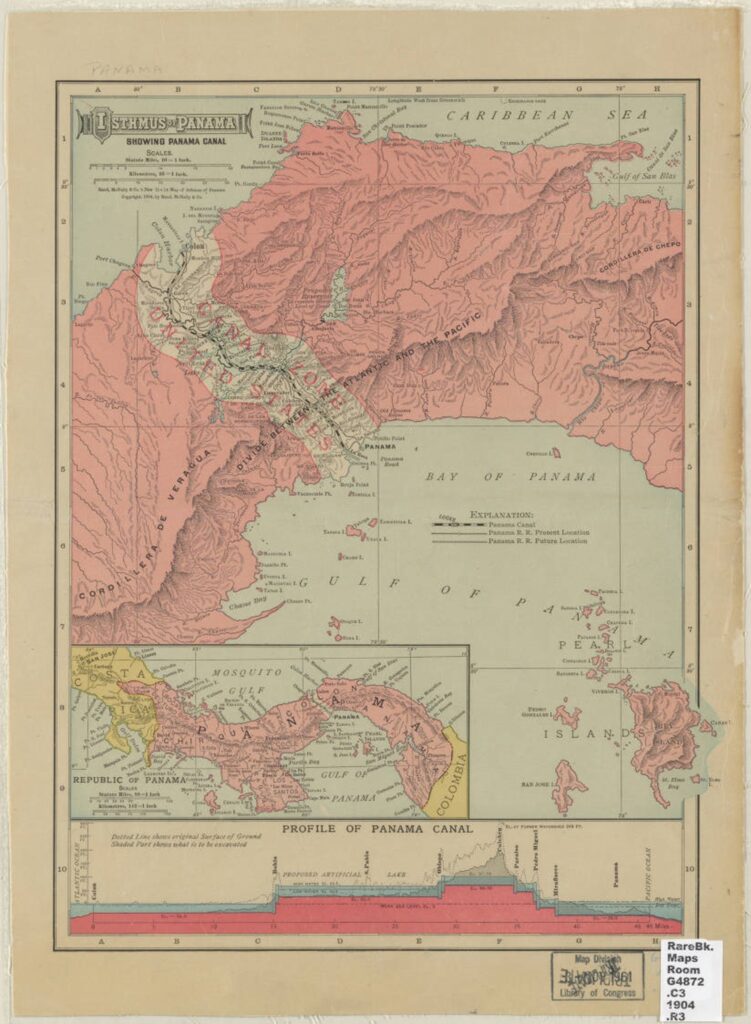

In November 1903, shortly after Panama declared its independence, United States Secretary of State John Hay and his Panamanian counterpart Philippe Bunau-Varilla signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty, granting the United States a 10-mile-wide strip of land to build a canal through the Panamanian isthmus.1 In return, the treaty stipulated the United States would make a one-time $10 million payment to Panama and an annual annuity of $250,000.2

This scenario was not easily won. Ever since the isthmus was discovered by European powers, there had been plans for a canal through the central American isthmus. This canal would link the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, which would reduce the cost of shipping and make the passage safer, the only alternative being the Strait of Magellan, an infamously dangerous route marked by large rocky outcrops and tremendous waves. A previous effort to build a canal was embarked upon by the United States and Great Britain in the 1850s (although this never made it past the planning stage).3 Another canal attempt made by the French began in 1880, but this effort fell apart in 1889 due to disease, death, and bankruptcy. In the wake of this effort, the United States sought to pick up the pieces and negotiate a new agreement with Columbia–of which Panama was a part at this point–to build the canal.

Although initial negotiations saw Hay sign a treaty with the Colombian Foreign Minister to allow for this, the financial terms of the agreement were unacceptable to the government in Bogotá, ending any chance of a deal.4 In response, Theodore Roosevelt sent warships to waters near Panama to tacitly support an independence movement that had been brewing there for some time.5 The success of this movement, and the newly independent Panamanians, provided the opportunity for Theodore Roosevelt and the United States to build their canal. After Panamanian independence was secured, the United States reveled in their accomplishment with Roosevelt saying that in pursuit of constructing the canal they could exercise “the equivalent of sovereignty” in the Canal zone.6 Although some hiccups were encountered, the U.S. company continued their work, allowing Theodore Roosevelt to visit the construction site in Panama in 1906. The Panama Canal was officially declared open several years later in 1914, during the Wilson Administration.7

Sources

1. “Panama Canal: History, Definition & Canal Zone.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 13 Aug. 2024, www.history.com/topics/landmarks/panama-canal.

2. Ibid.

3. “Building the Panama Canal, 1903-1914.” U.S. Department of State, U.S. Department of State, https://www.history.state.gov/milestones/1899-1913/panama-canal. Accessed 9 Sept. 2024.

4. Ibid.

5. Charles D. Ameringer; Philippe Bunau-Varilla: New Light on the Panama Canal Treaty. Hispanic American Historical Review 1 February 1966; 46 (1): 28–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/00182168-46.1.28

6. Letter from Theodore Roosevelt to William H. Taft. Theodore Roosevelt Papers. Library of Congress Manuscript Division. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/digital-library/o189559/. Theodore Roosevelt Digital Library. Dickinson State University.

7. “Panama Canal: History, Definition & Canal Zone.”

Entry contributed by Isaac Baker – Theodore Roosevelt Center Student Employee